Between November 12 and 29, I went on an expedition to the Subantarctic islands of New Zealand and Australia. Two and a half weeks on a ship through the Southern Ocean, hopping from island to island, watching birds and making photographs, away from civilization… it was a true adventure. I’m telling here the tale of this voyage.

****

In this phenomenal voyage, the Chatham Islands were in a category of their own, not the least because there we saw our first “regular” human inhabitants (I’m not counting the researchers on Macquarie here) in almost two weeks. House! Fields! Sheep (beurk)!

While the main island looks a lot like mainland New Zealand, where pastures have replaced the forest, the outlying groups offered more variety; some islets have even managed to remain predator-free! We encountered many endemic species, but the Black robin (Petroica traversi) eluded us. This small black bird has an extraordinary story, for in 1980 only five birds remained on Little Mangere, including only one breeding pair. A commando of conservationists managed to bring the species back from the brink by collecting eggs and giving them to Tomtits (Petroica macrocephala) for them to incubate and raise, forcing Black robins to lay more eggs and therefore increasing breeding success; that technique is called “cross-fostering”. Now 250 birds roam South-East Island and the Mangere Islands. This success story shouldn’t make us forget that, without having their habitat strictly protected, these birds would still be in grave danger (or extinct, probably).

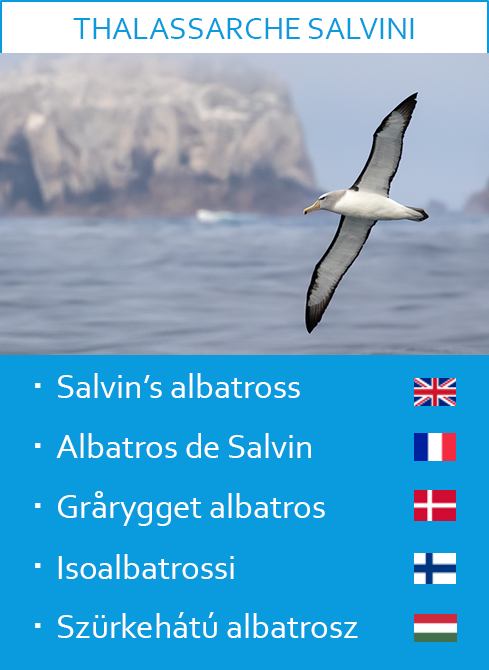

Our first glimpse of the Chathams came in the guise of a dark, pointy rock that hid in the fog as we approached it. Pyramid Rock is a haven for seabirds, and especially Chatham albatrosses (Thalassarche eremita), a species of mollymawk (the smaller albatrosses) that breeds exclusively there. Yes, on that small piece of land.

They are relatively safe there, with no rats to eat their eggs, but using only one location to breed makes them highly vulnerable to a localized disaster, like an oil spill. There again, conservationists have taken action, by abducting young albatrosses and placing them on a makeshift colony on the main island of the archipelago, feeding them by hand among statues of adult albatrosses until they flew away to the sea. Albatrosses come back where they are born to breed in turn, but it takes about five years for these ones to mature. Soon, we’ll see if the program worked, for the first chicks are set to return this year.

The last conservation story I want to mention is that of the Magenta petrel (Pterodroma magentae), or Chatham islands taiko. It’s not pink, mind you, but the first specimen was found on a ship called the Magenta, somewhere in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. No one knew where it had come from, and it took 111 years to discover that it bred on the Chatham Islands (and of course by then it was critically endangered…). Something had to be done, and an organization, now known as the Taiko Trust, was set up to protect a bit of forest on the main island, surrounding it with a predator-proof fence (like in Zealandia) to make sure no rat or cat could harm the “rarest seabird on Earth”. Nowadays, we know of only 19 breeding pairs.

We spent a day on the main island, and we met the people from the Taiko Trust. We walked in a valley where predators are controlled, and there we saw all the endemic bush birds we were looking for: Chatham gerygone (Gerygone albofrontata), Chatham pigeon (Hemiphaga chathamensis) and the local subspecies of New Zealand fantail (Rhipidura fuliginosa).

Some of us were supposed to then go to the reserve where Magenta petrels nest, to see a young one in an artificial burrow; alas, there was no bird, and the excursion was cancelled. Our only hope was to see an adult at sea.

For this, we set a chumming line up. Chumming is like giving sunflower seeds to your garden birds, but for seabirds: a frozen block of fish in a net is towed by the ship, while some delicious “fresh” fish slabs are sent to the water. Seabirds have a delicate sense of smell, and could pick us up from a distance. In no time, we had a horde of albatrosses and petrels in our wake.

Magenta petrels do not fancy the food we offered them (or they are too shy, no one knows), but we hoped that one would come out of curiosity, before flying away. There would be no time to climb from the inside if one was sighted, so all hands were on deck.

MAGENTA PETREL!

The call came from the upper level as we cruised along the coast, right in front of the nesting area. The rarest seabird on earth treated us with its presence, distant but well visible for half a minute. I mentioned it’s not pink; to be honest, it’s not even spectacular, with its garments of white and brownish grey, but it’s a bird, so it’s beautiful anyway ❤

That evening, no less than 6 (six!) Magenta petrels were sighted on the way to their burrows, possibly more than anyone has seen in their life except for those who study them. The day after, 3 more showed up, and even one was seen on the crossing to Dunedin the day after, for what might be the westernmost sighting of this species. Exciting stuff, and evidence that the guys on the Chathams do a wonderful work.

Our first zodiac cruise at the Chatham Islands had been along the shore of South-East Island, another one with fascinating geology. I vividly recall this rock hollowed like Swiss cheese, where we sighted White-fronted terns (Sterna striata) and Little penguins (Eudyptula minor), common species of mainland New Zealand that reinforced the feeling of déjà-vu, even though one can never tire of penguins, no matter their size or colour.

The first tick came as a surprise to me. Had I not read the programme well enough? I had already given up on the Shore dotterel (Thinornis novaeseelandiae), once a widespread wader in New Zealand, now critically endangered and restricted to some offshore islands… like the Chathams! We spotted several individuals on the rocky shore (hence their name). They are quite a pretty bird, aren’t they?

The second tick was the Pitt shag (Phalacrocorax featherstoni), a cormorant species that wasn’t named Chatham shag because that name was already taken (Leucocarbo onslowi)… Pitt shags actually seem to be much more common, and thus easier to find, than their counterpart, which are, guess what, a critically endangered species.

Fortunately, we managed to see both species, along with the Chatham oystercatcher (Haematopus chathamensis), a distinct endemic species that looks like any pied oystercatcher. I went to great length to capture an image.

There was quite a frenzy when the bird was spotted, but soon most of the people left, and in the end, only three photographers remained. One stood, one crouched… I lay down on my body, crawled and waited. When I was finally alone, the bird, distant at first, came to me and posed. I love these moments of trust, when the birds acknowledge you’re not a threat and go about their business. Sadly, another photographer came and it flew away. Well, at least I got a picture of myself covered in wet sand.

The last day was devoted to the Mangere Islands. No Black robin, as I said, but Chatham Parakeets (Cyanoramphus forbesi), albeit from a distance, showed well.

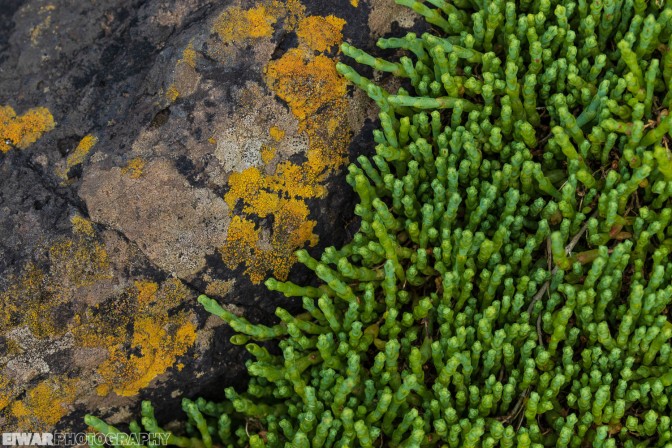

We cruised around the islands and stood in awe at the bottom of these majestic cliffs. Really, after the birds, rocks are the second stars of this trip (sorry elephant seal, you get the third spot I guess).

Previously in the SUBANTARCTIC series:

****

Follow me! Newsletter, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter… you name it!

Want to know where I am? Check out the map!

Want to support me? Buy a print!

****

Beautiful captures of land, sea and wildlife! Following your posts on your wild adventures lets me ‘tag along’ and I love it. 😊 Also love the photo of you, shows you get down and dirty for your fabulous shots. Awesome!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, one has to accept some discomfort to bring you this kind of photograph… laying down like that is actually quite alright, but it’s getting up, when the winds catches you wet and you’re putting sand all over your belongings, including the camera, that’s unpleasant 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great read, as always (pleased to see the jacket is well travelled and being put to good use)

LikeLiked by 1 person

You never thought it would end up tasting sand in the Chathams, did you? 😀

LikeLike

Some truly exciting sightings and gorgeous photos, Samuel. I liked Martha’s shot, too! 🙂 Really enjoying your record of this epic trip.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Samuel doing Samuel things in his natural habitat 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bonsoir Samuel

Au risque de me faire repérer parmi ces commentaires écrits en anglais, je t’écrirai en français. 😉

Superbes photos de cette merveilleuse destination à la faune et la flore…. extraordinaires ! Certains gros plans sont époustouflants. A des milliers de kilomètres de ce coin du monde, j’ai l’impression de sentir les embruns. J’adore également les fougères, que leurs frondes (feuilles) soient pleinement ouvertes, (un peu comme des panneaux solaires végétaux :-)) ou en forme de crosse.

Mille mercis pour ce bel article.

Cat

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pas de problème pour la francais, ca fait plaisir, et merci pour ce joli commentaire 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Au plaisir Samuel,

Je peine un peu à retrouver un rythme régulier de lecture et d’écriture mais bon… j’espère m’y remettre.

Catherine

LikeLiked by 1 person

Je connais ca. L’important c’est d’y prendre du plaisir !

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙂

LikeLike

Extra ! Super intéressant ! Tant pour les anecdotes de suivi qu’historique… tu as du te régaler. Les Chatham, ça a l’air d’être une étape importante du périple non ? Une sortie en mer dans ce coin ça dit envoyer ! 😀

Ta photo du manchot en noir et blanc est de toute beauté !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Merci Jérôme 🙂

Oui, c’est une étape importante, on y a passé trois jours je crois. Il y a beaucoup à voir !

LikeLiked by 1 person